“I think science entrepreneurs − and by that, I mean scientists who dare to commercialize their discoveries – are going to be the characters of the 21st century, those who are really going to change everything.”

By Đorđe Petrović

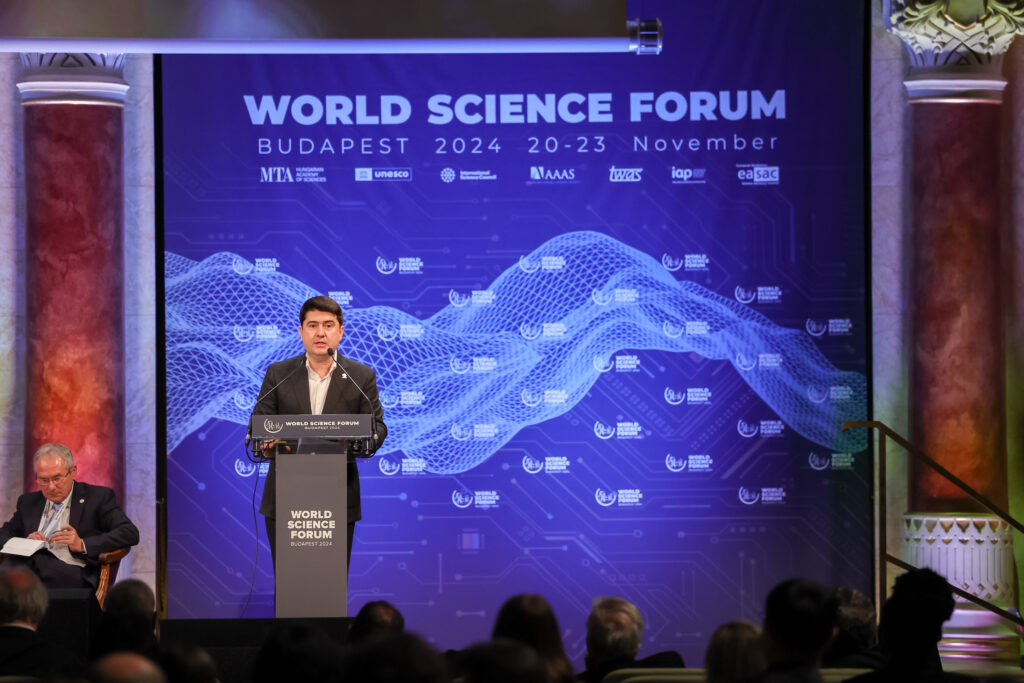

From November 20 to 23, 2024, the World Science Forum (WSF) was held in Budapest. This prestigious event successfully brought together scientists, decision makers, business representatives, members of civil society, and leaders of numerous international organizations. With more than 1,200 participants from 122 countries, the forum provided a platform for discussions on global science policies through a series of panel sessions and roundtable discussions.

On the third day of the Forum, special attention was drawn to the Third Ministerial Panel, held in the magnificent Pesti Vigadó Ceremonial Hall, on the left bank of the Danube. The panel focused on what must be done to adequately respond to the immense challenges the world faces today.

One of the most striking speeches during this compelling session was delivered by Dr Javier García Martínez, a professor of inorganic chemistry and director of the Molecular Nanotechnology Lab at the University of Alicante, Spain. He is also the founder of Rive Technology, a company through which he commercialized his groundbreaking scientific discovery—a new type of catalyst that reduces CO₂ emissions. In addition to being a distinguished scientist and entrepreneur, Professor García Martínez is a member of the International Science Council (ISC) and the World Economic Forum (WEF). Until recently, he also served as the president of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the Young Academy of Spain (YAS).

His inspiring speech at this year’s World Science Forum, in which he emphasized the indispensable role of young scientists and the transformative power of science, provided an excellent opportunity for an interview for Elementi popular science magazine. In the beautiful neoclassicist setting of Pesti Vigadó, we spoke with Professor García Martínez about his call to action, the role of the Global Young Academy (GYA), his innovative catalysts, and the importance of commercializing scientific discoveries.

During your address to the delegates earlier today, you made a call to action. Could you please clarify what you mean by that?

I wanted to convey a sense of urgency. We have to realize that while we are meeting here, we have many problems to deal with, just to name a few: war, hunger, climate change… real problems that affect millions of people, and we are very far from achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), so we don’t have the luxury of coming to a beautiful venue just to mingle. So my call to action was a message to move from rhetoric, from talking about things we already know, to an action plan. That is, a concrete plan with targets, milestones, resources… everything needed to make our recommendations a reality.

Scientists need to be much more practical if we are to make a difference, and we also need to involve all stakeholders. Policymakers, of course, but also industry. Without them, we will not move the needle. I would like to take this opportunity to highlight the key role of entrepreneurs in translating scientific discoveries into commercial reality, and thus in tackling our most pressing challenges with the best available science and technology. They are also a natural bridge between academia and industry, two communities that need to work more closely together.

My address to the plenary of the Forum was a call to action to get practical so that we do not leave Budapest without a clear plan on how to implement the recommendations we have discussed.

You also mentioned the Global Young Academy. You have been greatly involved in this organization. What is its mission?

Being a member of the Global Young Academy has had a profound impact on me, both personally and professionally. It is a great organization that gives a voice to early and mid-career scientists from all over the world, and that means giving them a seat at the table. For example, thanks to the great support of the Global Young Academy, many early and mid-career scientists are invited to speak at important meetings like this one, bringing their perspectives, their concerns and their own solutions. Early and mid-career scientists are the ones making the most fascinating discoveries, but also the ones who will live the consequences of our decisions. So, they must have a seat at the table, and the Global Young Academy gives them that opportunity.

Also, thanks to this international organization, there are now more than 40 national Young Academies, which are very much embedded in the science and technology ecosystems of the countries, helping government and industry to drive the science agenda forward. Until recently, I was the president of the Young Academy of Spain, so I know how important these organizations are for their countries and for young researchers.

A few years ago, you developed and commercialized novel catalysts that are now used by the chemical industry around the world.

When I was a post-doc at MIT, I discovered a new catalyst that reduces CO₂ emissions. So, I started a company, Rive Technology, to develop and commercialize this technology. By replacing existing catalysts with our nanostructured catalysts, which improve the diffusion of reactants into the interior of the catalyst, we significantly reduce the environmental impact of many chemical processes. It has been a long journey but, at the end, it has been a great success. In 2019, a major chemical company, W.R. Grace, bought our business. And now these catalysts are being used in chemical companies around the world, significantly reducing CO₂ emissions.

Why is the commercialization of scientific discoveries so crucial?

Because it shortens the time it takes for scientific discoveries to become real applications, solutions that can benefit people. We need entrepreneurs to take discoveries out of the lab and into the marketplace. Otherwise, many discoveries will never leave the lab and never solve the problems they can address. So, I think science entrepreneurs − and by that, I mean scientists who dare to commercialize their discoveries – are going to be the characters of the 21st century, those who are really going to change everything. If you think about it, the most important companies today – NVIDIA, OpenAI, Tesla – are no longer technology companies, they are science companies. They are making breakthrough discoveries in their labs and bringing the most advanced science to market, transforming or even reinventing entire industries. And who makes these great discoveries and brings them to market? Scientists. Scientists who discover and commercialize the solutions we need to create a better, more sustainable and prosperous future. Scientists who become entrepreneurs will be the great transformers of the 21st century.

Until a few months ago, you were President of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Can you tell us more about your role in establishing standards for digital data and developing chemical nomenclature tailored to AI?

More than a hundred years ago, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, IUPAC, was founded to create the common language of chemistry, the chemical nomenclature that we learned in high school. But if we want machines to be able to read, interpret and understand chemistry, we need a new chemical language that machines can process. At IUPAC, in collaboration with CODATA, we are developing an entirely new chemical language for machines. And that’s very important because it will accelerate the application of AI and machine learning to scientific discovery.

We also need digital formats, which means that the format in which scientific data is stored, managed and shared does not depend on the brand of equipment we use, but that we all use the same format. We are also working hard to enable machines to process scientific data. The quality, format and accessibility of data is key to AI, and we need universally accepted standards for this.

We are also working to ensure that all scientific information follows the FAIR principles of being findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. And we also need metadata, which is the data about the data, for example, how a scientific result was produced, the details of an experiment or the conditions under which it was carried out. It’s not just about the conversion or the yield; it’s also about how the experiment was done. This will help us to address the problem we currently have with the reproducibility of data. This is an aspect where metadata will be critical. At IUPAC, we are very committed to helping chemistry thrive in the digital space, and we are working hard to create the language, protocols and standards needed to do so.

As a world-renowned scientist, an entrepreneur and a leader in international organizations, what is your advice to young scientists?

When you are a scientist, you often feel that your career path is very narrow. You are either a science teacher, a university professor or a researcher. So it’s very limiting. Science opens many other doors. Dare to explore less trodden paths. I invite all scientists to discover all the possibilities that science has to offer, in education and research, of course, but also in science policy, in science communication, as a leader of a large organization, and as an entrepreneur. And remember, if you try something and find out later that it is not for you, there is nothing wrong with moving on to something else. The worst thing you can do is not to try. I always say that I am a better scientist now because I have tried many different careers in science. I have learnt a lot from each of the roles I have had, and I invite others to dare to discover all that science has to offer. You will be a better scientist and a more rounded person.

The interview was originally published in issue 39 of the popular science magazine Elementi, published by the Center for the Promotion of Science (Serbia).

Photo source: Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA)